First published in Rungh. Used with permission. http://rungh.org/primary-colours/

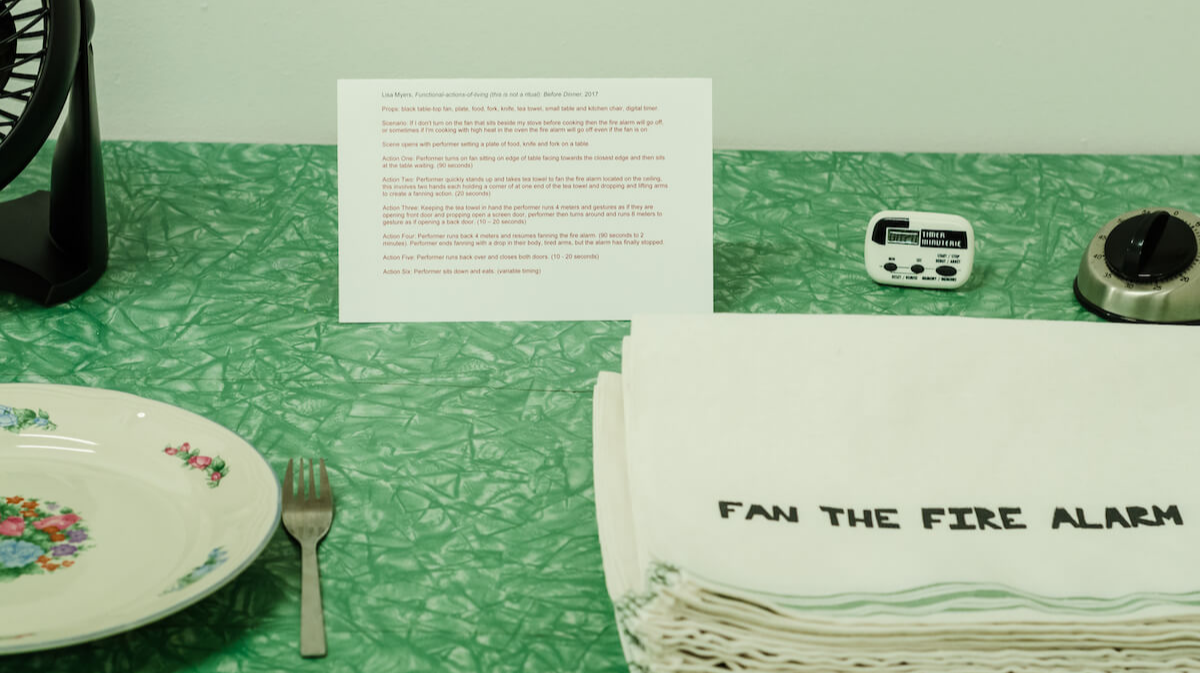

Lisa Myers. Fanning the Fire Alarm. 2017. Installation view.

Lisa Myers. Fanning the Fire Alarm. 2017. Installation view.

I attended the opening reception of Deconstructing Comfort at Open Space artist run centre in Victoria, B.C. in conjunction with the Primary Colours/Couleurs primaires (PC/Cp) gathering on Lekwungen Territory that brought together over eighty participants from across Turtle Island, traversing the imposed boundaries of colonial nation states. The stated aim of the event was to centre Indigenous artistic practices within the Canadian art system and assert the critical place of artists of colour in any imagining of Canada’s future(s).

The gathering assembled artists and cultural workers from across disciplines, generations, and cultures, and was effectively organized to prioritize those conversations the invited participants felt were most urgent within the sector. Topics ranged from Indigenous protocol and the transmission of knowledge, cultural appropriation as knowledge extraction, and two sessions on the intersection of Black and Indigenous experiences from both dialogic and movement-based approaches.

The curators of the Deconstructing Comfort exhibition were variously involved in PC/Cp, including France Trépanier, co-organizer of the gathering with Chris Creighton-Kelly and Aboriginal Curator at Open Space; Doug Jarvis, Guest Curator at Open Space and PC/cp attendee, and Michelle Jacques, Chief Curator at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria (AGGV), who was called upon to be a witness of the gathering. The exhibition notably stands within an ongoing collaborative relationship between the AGGV and Open Space, including the co-presentation of exhibitions like Anna Banana: 45 Years of Fooling Around with A. Banana (2016-16), and programs such as Red Words: A Conversation on Indigenous Performance with Chris Creighton-Kelly, James Luna, and Amy Malbeuf. These collaborations, although often modest forms of support between institutions with limited resources are integral to supporting a vibrant—and substantively diverse—artistic community in the city of Victoria.

Nadia Myre. A Casual Reconstruction. 2017 Installation view.

Nadia Myre. A Casual Reconstruction. 2017 Installation view.

No exhibition stands alone, and it is from the curators’ ongoing commitment to collaboration that Deconstructing Comfort emerged. In the exhibition brochure, the curators speak to a process-based approach of working with artists who interrogate “spaces of [dis]comfort to generate transformation and change.” In lieu of a curatorial essay, the brochure contained a word map with terms such as “HEALTH,” “BODY,” “LANGUAGES,” and “LAND” linked to short quotes from participating artists and intersecting concepts that illuminate complex entanglements of being in relation colonialism, capitalism and bridging cultures. This web was reflected in the exhibition itself, with many of the works themselves being process-based.

Haruko Okano. Homing Pidgin. 2006/2017. Installation view.

Haruko Okano. Homing Pidgin. 2006/2017. Installation view.

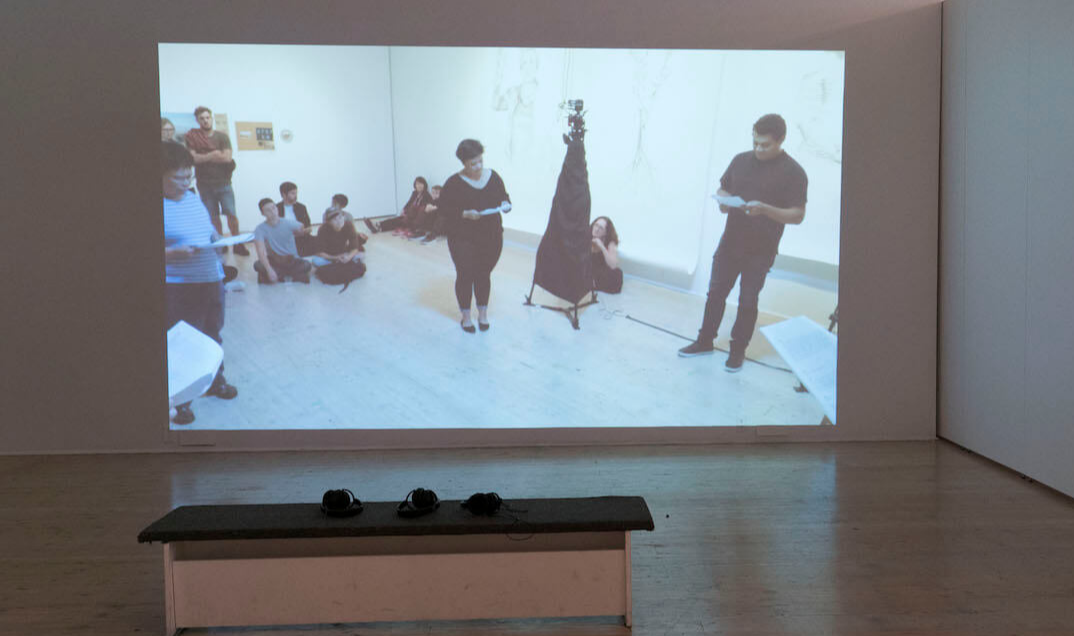

Both Nadia Myre’s A Casual Reconstruction (2017) and Lisa Myers’ Fanning the Fire Alarm (2017) utilized participants to perform or activate the work. In A Casual Reconstruction, Myre invited an intergenerational and cross-cultural group to read a transcript of a dinner conversation between the artist, her colleagues and friends on the experience of being mixed-raced Indigenous, particularly in the French Canadian context, of the differences of living on and off-reservation, of the way in which speaking ancestral languages (or not) shape our worldview. Inhabiting voices not their own, the performance—recorded in the gallery and edited into a video work—engendered an empathetic experience and frank understanding of complex, specific and lived experiences of Indigeneity.

Myers’ work similarly provided a "script" in the form of a set of instructions for gallery visitors to follow in exchange for a tea towel emblazoned with the work’s title. The actions included setting a timer, fanning a fire alarm for a specified amount of time, and running across the gallery to “open” and “close” screen doors before finally being able to sit down at a table set for dinner. Performing the instructions was an absurd and isolating yet mundane experience in which the participant becomes a spectacle of everyday dysfunction.

Leuli Eshraghi. tagatanu’u. 2017. Performance site image.

Leuli Eshraghi. tagatanu’u. 2017. Performance site image.

Language and food were also significant connecting threads throughout the exhibition. From Myers’ set of directives meant to reveal systemic inequalities in everyday experiences, Haruko Okano’s Homing Pidgin (2006/2017), which also included a table with place settings, documented a Japanese-Canadian pidgin language specific to B.C. in the 1880s to 1900s. Pamphlets with the translation of terms between Japanese, the Pidgin language, and English, accompanied magnetic words arranged on plates with metal chopsticks. Visitors were invited to create a dialogue on the plates, using language specific to the region and the people that came to call this place home.

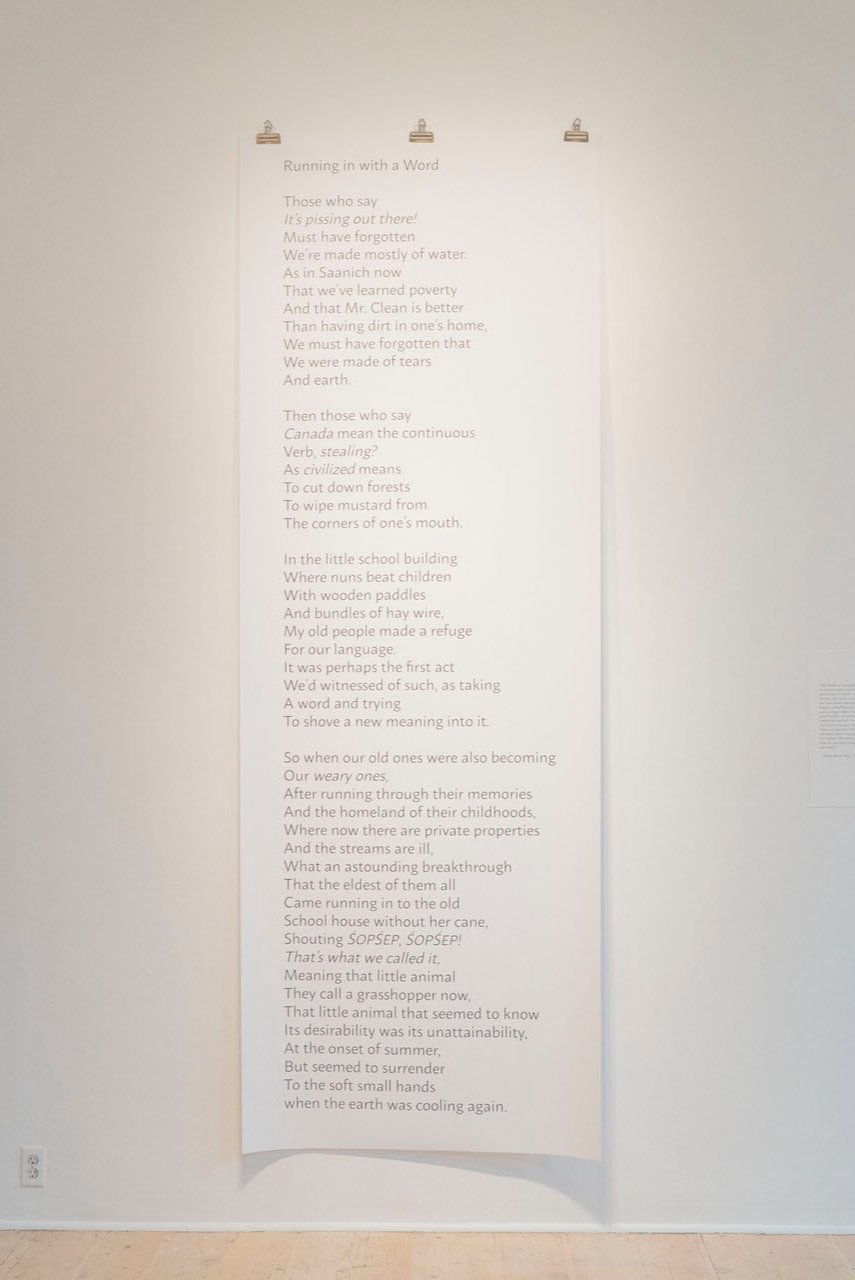

Phillip Kevin Paul. Running in with a word.(2017). Installation image.

Phillip Kevin Paul. Running in with a word.(2017). Installation image.

In Léuli Eshrāghi’s performance and installation tagatanu’u (2017), the artist read in Sāmoan, Hawaiian, French, English, Tałtan, Secwepemctsin, Nuxalk, Ńsyilxceń, Woi Wurrung, Anishnaabemowin, and Latin as he moved through the audience handing out macadamia nuts and drinking boxed coconut water.

Eshrāghi’s performance wove a complex narrative of belonging across displacement and diaspora, Indigenous lands and languages his own and others, and paralleled to the commercial flow of goods as exoticized objects of desire. Confronting the colonial desire for consumption with the desiring Indigenous body opened space for both expansive and specific possibilities of being.

Jamelie Hassan's assemblage of objects, photographs and text shared a resonant story of belonging across vast expanses. al Haq al Canadiyaa (2017) tells of Hassan’s time spent in her father’s ancestral village in Lebanon, where she was often invited to share an early morning breakfast with two women. They would tease her about who was “al Haq al Canadiyaa” (the true Canadian), not understanding at the time that the women were Cree sisters from Lac La Biche in Northern Alberta who married two Arab brothers and came to live in the village. As part of the PC/Cp events, Hassan served a traditional Lebanese breakfast of apricot jam, bread, cheese and tea outside the hotel, inviting the residents of a nearby tent camp to join. These lived experiences place the notion of “the true Canadian” into a perspective wholly apart from the rhetoric of nationhood encountered through the lens of settler colonialism.

Phillip Kevin Paul’s poem included in the exhibition, Running in with a word (2017), similarly contrasted settler colonial narratives with knowledge arising from ancestral language. The poem moved between forgetting and remembrance: a forgetting forced onto young children in the residential school, where disconnection from language meant disconnection from meaning in relation to culture and the living beings of the earth, and a remembering sparked by the smallest creature—the grasshopper—moving a grandmother to run through the school house shouting “ŚOŚEP, ŚOŚEP! / That’s what we called it”.

Finally, Syrus Marcus Ware’s Activist Portrait Series (2017) are monumental portraits of activists from Black Lives Matter Toronto, of which Ware is a Core member. The exhibition at Open Space included three works: Antoinette Davis, Cotton, with roots and Portrait of Cynthia Garrett. Rendered in graphite on paper, the large scale portraits are labour intensive and loving depictions of community members whose own labour in the struggle toward rights and equality, and against systemic violence, is itself monumental. Ware marks this ongoing struggle with his first plant portrait in the series, the cotton plant standing as a signifier of both intergenerational trauma and resistance.

Syrus Marcus Ware. Activist Portrait Series. 2017

Syrus Marcus Ware. Activist Portrait Series. 2017

Marking, honouring, remembering and retelling stories were aspects of Deconstructing Comfort that exceeded the title chosen for the exhibition. Although confronting histories of settler colonialism, the Transatlantic slave trade and ongoing violence against marginalized communities, the works in the exhibition were more impactful in terms of their unique, situated perspectives, their insistence on the specificity of experience as being a worthy place from which to speak, and to thrive. In this way, the exhibition as a whole was arguably constructing as much or more than it was deconstructing.

Tarah Hogue is a curator, writer and uninvited guest on xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwu7mesh (Squamish), and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) territories/Vancouver, B.C. where she has lived since 2008. She is a member of the Métis Nation of Alberta and was raised in Red Deer, A.B. on the border between Treaty 6 and 7 territories. Hogue is the inaugural Senior Curatorial Fellow, Indigenous Art at the Vancouver Art Gallery and is a Visiting Curator at the Institute of Modern Art in Mianjin Brisbane for 2018. She was curator-in- residence with grunt gallery between 2014–2017, the 2016 Audain Aboriginal Curatorial Fellow at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, and has curated exhibitions at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Or Gallery, and SFU Gallery. She is co-organizer of #callresponse with Maria Hupfield and Tania Willard, currently touring through 2019. Hogue has written texts for BlackFlash, Canadian Art, Decoy Magazine, Inuit Art Quarterly, and MICE Magazine.