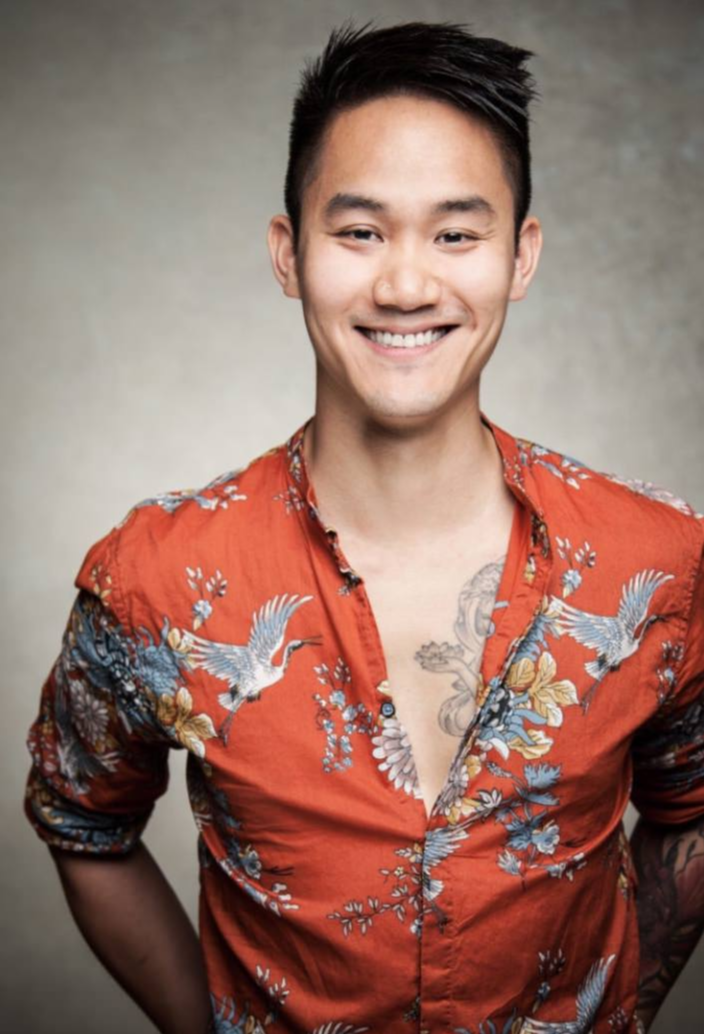

Untitled diptych from "Yellow Peril: Queer Destiny"

Untitled diptych from "Yellow Peril: Queer Destiny"

Introduction

Over the past few years, there has been a surge of anti-racist organizing within contemporary queer politics in Canada. The resurgence of queer Asian activism across the country, alongside the organizing by Black Lives Matter Toronto and Vancouver against police participation in pride parades, and the movement against Israeli pinkwashing – are just some of the many recent examples of anti-racist organizing that is happening in queer Canada today. During this political moment, I co-founded Love Intersections, a collective of queer artists of colour, whose primary mandate is to illuminate the lives of marginalized queer voices in our communities. Love Intersections emerges amongst many other queer artists of colour, who are using the arts to interrogate hegemonic social formations, including the legacy of colonialism, systemic racism, and cisheteropatriarchy. Queer artists of colour have been grappling with how to actualize the discourses of “anti-racism”, “decolonization”, along with a desire to contend and mandate practices of “intersectionality”.

The term “intersectionality” was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw to express the exclusion of black women’s lived experiences within the Second Wave feminist movement (Crenshaw, 1989). Patricia Hill Collins, Audre Lorde, and bell hooks, were also amongst the many black feminists who argued that the experiences of oppressive power (i.e. patriarchy), is not singular, and is experienced differently, through a multiplicity of intersections. The experiences of systemic racism from colonialism can intersect with patriarchy and cisheteronormativity, for example, to create various social barriers and inequities for people of different identities.

Today, “intersectionality” has emerged as a popular lens for social justice activists to employ in order to interrogate hegemony within various social movements. It is nearly impossible to encounter any progressive activist groups today that do not include some form of “intersectionality” in their mandates and/or programming. “Intersectionality” suggests that our lived experiences are made up of a multiplicity of “intersections”. So for example, I am not only a queer person, I am also a cisgender, man, of Chinese descent. These different intersections form the way I encounter the world; an experience that shifts depending on geography, socio-political context, space, and time. On paper, intersectionality allows us to grapple with the multiple experiences of oppression (and privilege) that affect us systemically. For example, in many cases, my experience as a femme, gay, Chinese person means that in many spaces in the world, my safety, security, social mobility is affected by these intersections of identity. However, being cisgender, male, able bodied, and having been able to afford graduate level post-secondary education, affords me certain privileges and social currencies to navigate the world more easily than those who may not have these privileges.

Intersectionality is at the heart a tool to explore and grapple with positionality, and where we are situated in the world, compared to those around us. It’s a tool that allows us to contend with oppression and privilege, and has particular relevance in queer politics in Canada today, as the community continues to work on ongoing issues of systemic racism in the community. Translating these theoretical conceptions of intersectionality into praxis is something that many queer organizations are working towards. This essay is an exploration of the possibilities of intersectional praxis, and how artists of colour have been engaging with this discourse to create social shifts.

How do queer artists of colour conceptualize intersectionality as praxis for transforming communities through artistic practice?

This essay will take up these crucial issues through an autoethnographic exploration of my own experiences forming Love Intersections, and our ongoing relationship with the Vancouver Queer Film Festival. The following will be an investigation of how two queer organizations strive to incorporate notions of intersectionality in their work. As one of the co-founders of Love Intersections, I will also study some of the philosophies that Love Intersections has developed over the past few years that attempts to materialize a politic of intersectionality beyond theory and lip service.

Finally, as a queer artist of colour myself, it is impossible to move forward with a research project that is so close to my own lived experience, without incorporating my own practice and lived experience into the body of research. Using methodologies developed through feminist autoethnography, I will also situate myself within the research, and contend with my positionality within this discourse, as a queer artist of colour doing anti-racist work in my artistic practice.

Intersections of identity

In the spring of 2014, the Vancouver School Board started the routine process of updating its anti-discrimination policies. On the table was the anti-homophobia policies that were over a decade old. The City of Vancouver’s Pride Advisory committee had some suggestions to expand the policy to be inclusive of transgender and gender non-conforming people, and suggested a policy to have at least one, single stall, gender neutral bathroom in each school. News of these policy updates to protect the safety of trans students caught the wind of evangelical Chinese Christians, and the policy update erupted into a huge, divisive controversy.

At the time, I was working for Out in Schools, which is a program that teaches anti-oppression workshops throughout BC. Out in Schools had a seat on the Pride Advisory Committee, and my colleague Jen Sungshine and I were a part of a coalition of queers and allies that were supporting the trans inclusive policy. The controversy around the policy affected us at a personal level. As people of Asian descent, and as someone who grew up in the evangelical Chinese community, I felt quite conflicted with seeing people who were opposed to the policy who “looked like” me. At the same time we started hearing racist comments from our queer (predominately white) allies, such as “What makes your people and your culture so conservative?”. We were frustrated at the way that these comments erased our own identities, as queers who are also racialized. This story is a microcosm of wider systemic issues that we faced in the queer community, including the underlying pressure to erase your ethnocultural identity when you come out, and become assimilated into the mainstream Eurocentric community.

The media reports on the controversy also brought issues of representation to the surface; with much of the focus in the media, on the “ethnic Chinese” identity of the evangelical Christian protestors. To put this in perspective, several months prior, a group of predominantly white evangelical Christians protested a similar policy in a different community, yet the media reports mentioned nothing of the ethnic identities of these white/Anglo-Saxon protestors. This difference in media representation of racialized communities is yet another example of how white normativity operates by racializing communities of colour, in order to in turn find ways to marginalize them.

We decided to do something about our frustrations, and formed Love Intersections out of a desire to share the layers of identity that make up who we are. What are the stories that make up our ways of being? How do different encounters with hegemonic power structures: homophobia, colonialism, colourism, ableism, inform our lived experiences? How do our identities meet with different lived experiences at different intersections? How do we operationalize “intersectionality” in our artistic practices, so that we don’t reproduce oppressive narratives of marginalized voices?

At the time that this controversy at the Vancouver School Board erupted, I was working as the Outreach Coordinator for Theatre for Living – a grassroots social justice oriented interactive theatre company based in Vancouver. After discussing the controversy in the office, Theatre for Living offered to hold a “theatrical dialogue”, using a theatre technique called a “Rainbow of Desire” to bring the opposing sides together, to humanize each other. The methodology of “Rainbow of Desire” is not to change the opinions of either side, but rather, to capture a moment of solidarity – albeit fleeting, and often minute – between two opposing sides. We observed that a moment of solidarity between the two sides was that parents on both sides loved their children, and also wanted their children to be safe, and that perhaps there were ways that we could use the arts to build community instead of building barriers. This philosophy inspired part of our desire to find ways to operationalize intersectionality, and also began a personal journey to find ways to work collaboratively and intersectionally with communities. Many of our philosophies that we developed for our arts practice at Love Intersections was inspired by the philosophies of Theatre for Living.

Intentional Intersections

In developing intersectional protocols for our artistic practice, one of our main contentions was the ways that intersectionality has been appropriated by neoliberal notions of “diversity and inclusion”. “Diversity and Inclusion” has translated at a broad level, to tokenistic gestures of bringing in bodies and identities that are marginalized, without actually implementing transformative policies that address the underlying issues of white supremacy and systemic racism. For example, affirmative action quotas for diversity are meant to address the imbalance of representation in organizations, but the deeply rooted structures in the organizations that reinforce systemic racism, remain unchanged. I would argue that in fact, Eurocentric normativities become even further entrenched through tokenistic forms of affirmative action, in that it becomes a way to excuse the silencing of resistance.

To address this, we recognized that the static approach to engaging with identity politics was one of the main issues, and so we adopted an approach that would focus on relationships, as a way to keep our policies and arts practice malleable to address the needs of community. While neoliberal pressures demand economic returns for the inclusion of marginal identities, we need to find ways to engage around issues of oppression and marginalization that are not only transactional.

In our arts practice, this has translated into a few core philosophies:

- Focusing on process: Designing projects that have a predetermined end goal creates restrictions on how we can work collaboratively with communities. In our desire to be accountable to the voices we include in our projects, our practices have to be able to be responsive to our collaborators and their communities. That means, being open to completely changing the outcome of the project, if that is what the community desires. As filmmakers who are using arts to literally represent people's stories, we are fundamentally accountable to the communities we work with.

- Doing work by invitation: Because we are often outsiders to the communities we are working with, we wanted to find ways to be responsible and accountable to the narratives that we were creating through our art practice. Rather than “parachuting” into communities and deciding what stories need to be told (and how to tell them), we do work when invited by communities. To do this, we decided to ensure we developed an approach to focus on outreach to build genuine, reciprocal, and accountable relationships with communities. Through doing work by invitation, we can meet communities where they are.

- Working in collaboration: linked to the above point on invitation, we also unequivocally work in collaboration with people and communities. Too often, artists who are not from a particular community appropriate stories that are not their own, and exploit communities for their own benefit. Because our work is quite literally representation of people’s stories, it is fundamental that we engage with the our participants in a real and genuine way. That means giving directorial and veto rights to our participants – even if it means risking financial resources. This process of working in collaboration with communities allows for intersectional nuances to be brought to the surface, in a way that would have been impossible otherwise.

Intersections of Trust and Accountability

Putting intersectionality into practice is ultimately a call to action. It’s always political, because our identities are political. When we made our film “Amar: Deaf is an Identity”, and “Loving our Language: Pride in Disability Culture”, we collaborated with our friend (and now board member), Amar Mangat, to make a film about his own intersectional identity as someone who is queer, Deaf, and South Asian. During post production, Amar noticed that the visibility of his signing was not ideal because he was not wearing black (which is custom for signing on camera), and requested that we find a way to fix the signing issue. Since none of us knew American Sign Language, or were familiar with Deaf culture, it would have been ignorant of us to have made this film without collaborating closely with Amar. We would have never caught what for us looked like subtle nuances, but for Amar, and for folks who are Deaf and use ASL, are important cultural characteristics that we would have misrepresented in the film had we not made the film in collaboration with Amar.

I also spoke with friend and colleague Anoushka Ratnarajah, Artistic Director of the Vancouver Queer Film Festival, about her approach to intersectional community accountability, curation, and reconciliation. The Vancouver Queer Film Festival has been a supporter of Love Intersections since our inception, and Anoushka invited Love Intersections to be the local Artist in Residence for the 2018 festival season. Using the artistic medium of film as a case study in particular, Anoushka discussed with me the history of film, and its roots in photography and cartography. Photography was initially created to make visual representations of the world to the public, or to share a particular truth, which makes the medium inherently biased to the practitioner who has to make decisions. Furthermore, the actual development of film itself has a history of literally not being able to “see” people of colour, because the light range it was originally created for was made to read only white skin (Ratnarajah, 2018).

Colonial history and white supremacy also intersect with the history of film, in that the representations of bodies in film, have also reflected the political systems that have maintained power through imperialism. The history of Blackface - where white actors would paint themselves as black minstrels and perform racist caricatures of black slaves – is another historical example of how film originally portrayed whiteness as more desirable than black bodies. These issues continue to be pervasive today. Only 31% of film leads in Hollywood today are women, and 13.9% people of colour (Ramón et. al, 2018). Additionally, people of colour tend to be typecast into certain roles, which uphold racial hierarchies, stereotypes and other social inequities.

The aforementioned issues of intersectional accountability is deeply relevant in the film and media arts community. Within this context of colonial subjugation faced by people of colour, Anoushka also discusses the need for reparations, along with representation, and representation as a form of reparation. “Part of my philosophy in making curatorial decisions is not just making sure that people of colour are represented, but taking it one step further and finding ways to make people of colour, Indigenous folks, and other marginalized identities and bodies more visible than cis, white bodies. I see this not only as a form of reparation, but also a way to shift power and privilege away from what has been historically maintained.” (Ratnarajah, 2018).

How does this discourse on accountability take shape in our own intersectional artistic practices?

Engaging in processes of collaboration and listening, allow us to engage in journeys with our communities, that then allow us to interrogate power and inequity. “I think one thing that is important (especially as a curator) is to have humility, and recognize that you don’t have to know everything.” (Ratnarajah, 2018). Forging reciprocal partnerships with communities and community members with lived expertise can be a way that we strive towards making our work accountable. Reciprocity is also a key way that we can transform our relationships away from transactional relationships, and can ground our solidarities towards transformation. One approach that we employ (that we learned through Theatre for Living), is to engage in reciprocity in a way that our arts practice serves communities. This intention means that we must continually check power dynamics, so that we strive to ensure that our artistic practice indeed serves the communities we collaborate with.

As artists of colour who are settlers on unceded Indigenous territory, the notion of accountability is something that we continue to grapple with as artists who strive towards intersectional praxis. As settlers here, we actively participate in the continued subjugation and extraction of Indigenous resources, land, and culture. “By being settlers here on unceded Indigenous lands, we have alignment with the white supremacist state that benefits us, and directly takes away from the rights of Indigenous people.” (Ratnarajah, 2018). Because of this, engaging in processes of decolonization, and understanding our positionality as settlers must be part and parcel of endeavours towards intersectional praxis. How are my relations with Indigenous communities? Does my arts practice serve to benefit justice for Indigenous communities? How can I be more accountable as a settler to Indigenous people? These are just some questions that have permeated from our own grappling with privilege as settlers of colour.

Intersections of Love

When we were developing branding for the media arts collective (that would eventually become Love Intersections), we wanted to find language that would not only capture our political/anti-racist intentions around intersectional praxis, but also our intentions. What is the desire behind wanting to employ intersectionality as arts praxis? At the heart of our intentions for social transformation is a deep love for our community, which ultimately is made up of different people we have relationships with. Grounding this into our arts practice was important to us because we did not want to lose sight of our intentions behind our strive towards intersectional praxis – an intention of love – which is ultimately why we decided to name our organization “Love Intersections”.

The notion of “love” also suggests philosophical underpinnings to the discourse of intersectional praxis that has been discussed through this article. While love can be described as an intention, the relational aspects of love implore us to take up the work to make our relationships accountable, respectful, and reciprocal. Love also takes work, which includes engaging in processes of accountability. This work also happens continually, and requires constant attention to power, and the ways that privilege and oppression play out under the white supremacist, colonial system in which our artistic practices take place.

References

Hunt, D., Ramón, A., Tran, M., Sargent, A. & Roychoudhury, D. “Hollywood Diversity Report 2018: Five Years of Progress and Missed Opportunities”. UCLA College of Social Science Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. 2019. Los Angeles.

Crenshaw, K. 1989 “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” The University of Chicago Legal Forum. 140:139-167.

Latif, Nadia. “It's Lit! How Film Finally Learned to Light Black Skin.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 21 Sept. 2017, www.theguardian.com/film/2017/sep/21/its-lit-how-film-finally-learned-how-to-light-black-skin.

Ratnarajah, A. Personal Interview. 8 November 2018.

Smith, David. “'Racism' of Early Colour Photography Explored in Art Exhibition.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 25 Jan. 2013, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/jan/25/racism-colour-photography-exhibition.

David Ng is a queer feminist, and is the co-founder of Love Intersections, a media arts collective made up of queer artists of colour. David is a passionate social justice advocate, and has co-founded and worked on numerous arts based anti-oppression campaigns and projects ranging from feminist anti-violence campaigns, decolonization work, cultural safety, anti-racism, and other forms of social justice art and activism.

Banner image: provided by David Ng. FromYellow Peril: Queer Destiny.